1. How do we accelerate a particle?

In mechanics we usually talk about acceleration, but for a particle accelerator the more relevant question is: how do we increase the kinetic energy of a charged particle? In other words, we do not primarily “accelerate”, we energize.

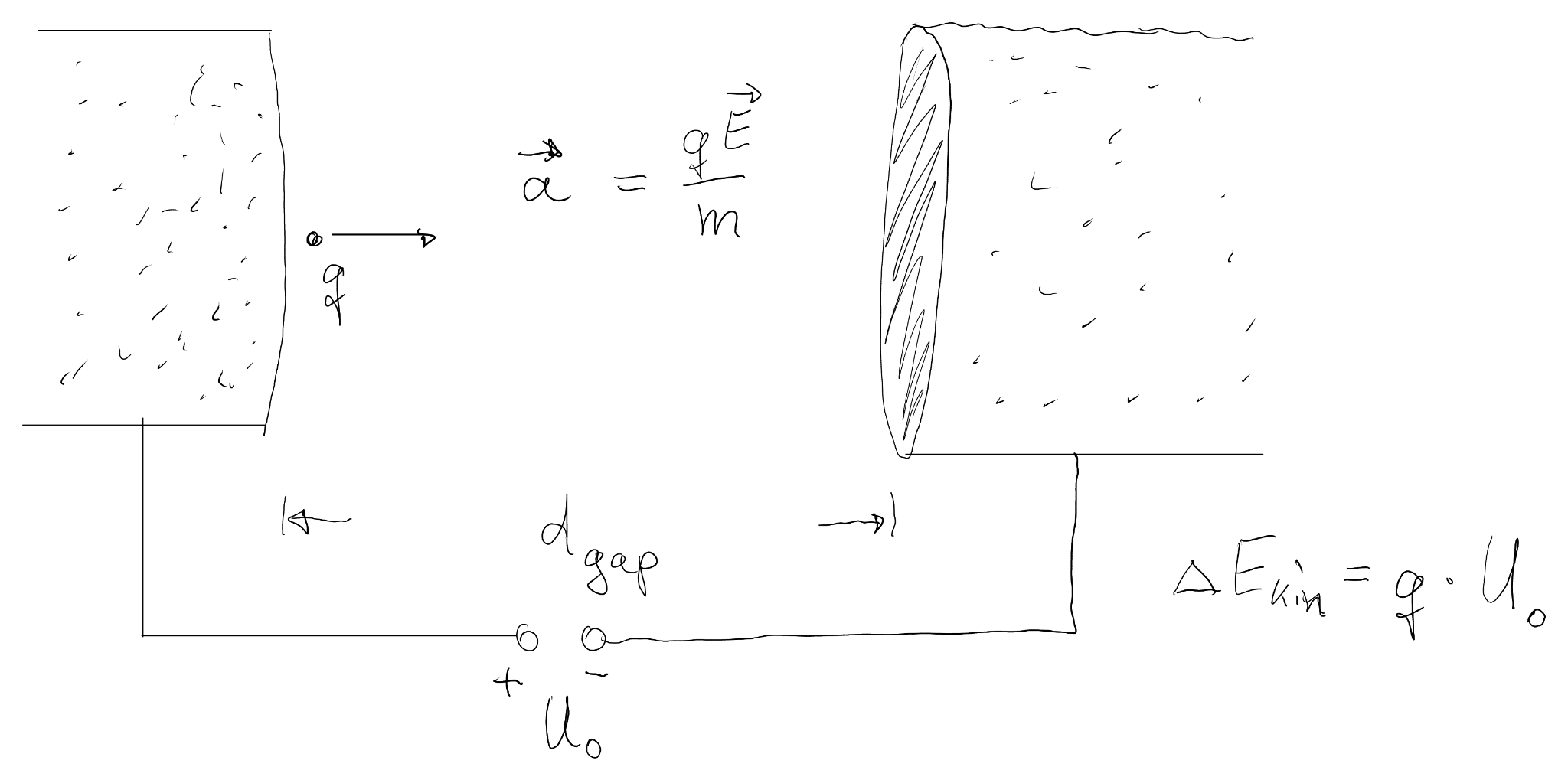

The starting point is Newton's second law, \( \mathbf{a} = \mathrm{d}\mathbf{v}/\mathrm{d}t = \mathbf{F}/m \). For a particle with charge \( q \) in an electric field \( \mathbf{E} \) we have \[ \frac{\mathrm{d}\mathbf{v}}{\mathrm{d}t} = \frac{\mathbf{F}}{m} = \frac{q}{m} \mathbf{E}. \] In a homogeneous field \( \mathbf{E} \), the motion is uniformly accelerated along the field direction.

The kinetic energy gain follows from the work done by the force: \[ W = \Delta E_{\text{kin}} = \int_A^B \mathbf{F} \cdot \mathrm{d}\mathbf{s} = q \int_A^B \mathbf{E} \cdot \mathrm{d}\mathbf{s}. \] For a constant field between two electrodes, i.e. a parallel-plate capacitor, this simplifies to \[ \Delta E_{\text{kin}} = q U, \] where \( U \) is the potential difference between the plates. This motivates the electron volt as a convenient unit: 1 eV is the kinetic energy gained by an electron when it traverses a potential difference of 1 V.

Note that this relation continues to hold in the relativistic regime: the kinetic energy is then \[ E_{\text{kin}} = m c^2 (\gamma - 1), \qquad \gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - v^2/c^2}}, \] but the work done by the electric field is still \( q U \) between two electrodes.

2. Limits of constant-voltage (DC) accelerators

A straightforward way to energize charged particles is to build a very large DC voltage source and let the particles fall through the corresponding potential difference. This is the idea behind electrostatic accelerators such as the Van de Graaff generator and its tandem variants.

Robert J. Van de Graaff developed the belt-charged electrostatic high-voltage generator around 1930; his work was first widely reported in 1931, and larger machines followed within a few years. By the early 1930s, electrostatic accelerators reached hundreds of kilovolts to a few megavolts, and later up to about 10 MV using pressurized tanks with insulating gases such as SF\(_6\). These machines are still in use as precise low-energy ion accelerators.

The real limitation is not the mechanical design but the maximum breakdown field that the electrodes and the insulating medium can withstand. Above a certain electric field, microscopic surface irregularities, field emission and gas ionization trigger discharges that quench the field. Operating closer to this breakdown limit allows higher gradients but increases the probability of destructive sparks.

Side note: physical picture of breakdown

In gases, breakdown often starts with ionization of residual atoms by field-accelerated electrons, leading to an avalanche and a conducting plasma channel (Paschen-law-like behavior). In vacuum or at metal surfaces, breakdown tends to be initiated by microscopic field emitters and surface defects; local enhancements of the electric field lead to intense emission, heating and eventually the formation of a plasma arc.

Experiments show that the effective breakdown threshold depends on many factors: material, surface preparation, pulse length and frequency. Generally, higher-frequency RF structures can sustain significantly larger gradients than comparable DC setups, but there is no universal power law (such as a simple \(E_{\text{bd}} \propto f_0^n\)) that holds across all technologies.

3. Using AC voltages: a single RF gap

Technologically, high voltages are much easier to obtain with AC than with DC, because transformers efficiently step up AC voltages. This raises an important question: can we use an AC voltage to accelerate particles in a capacitor?

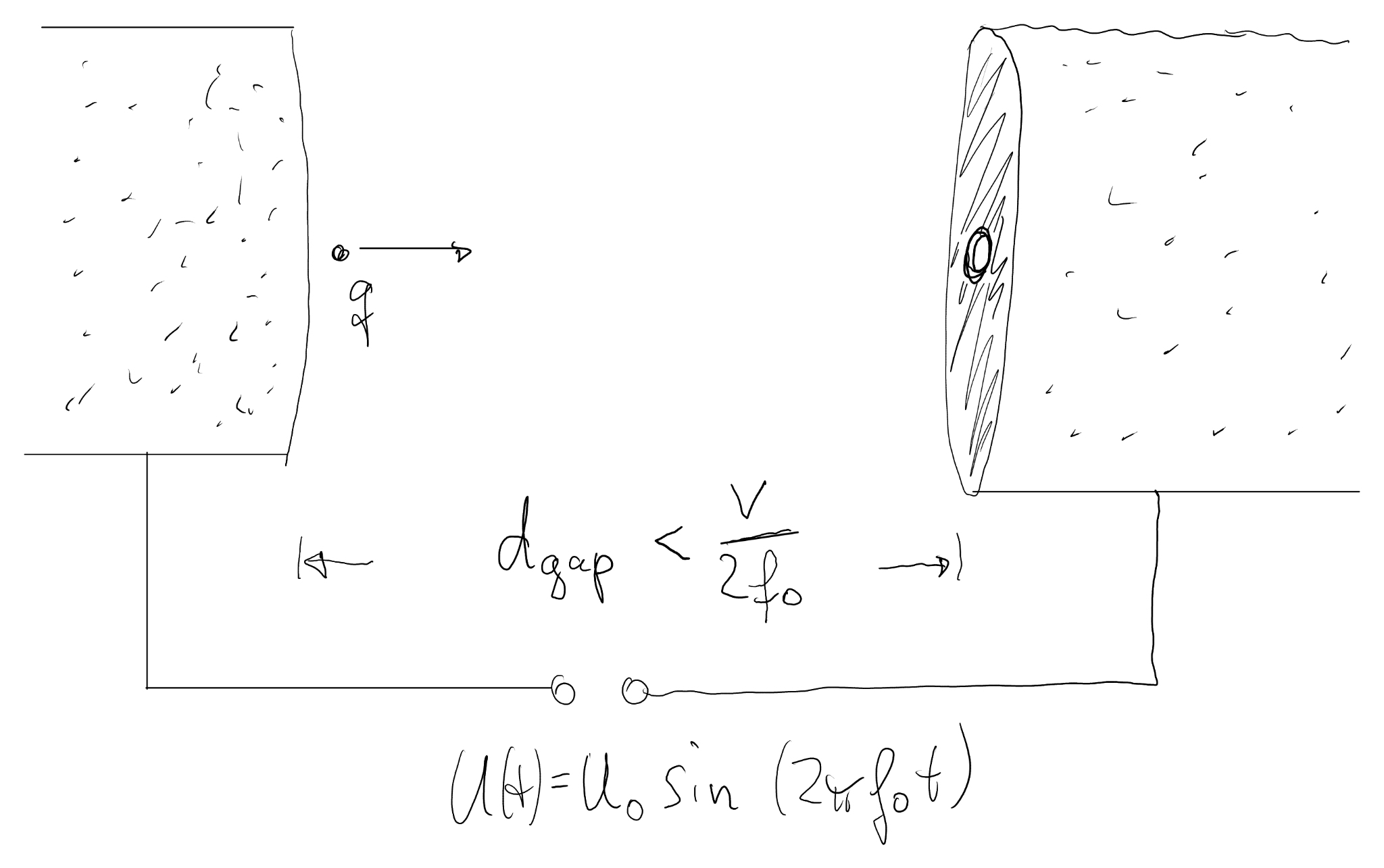

We consider the same parallel-plate geometry, now with a small exit aperture in the right-hand plate and a sinusoidal voltage \[ U(t) = U_0 \cos(2 \pi f_0 t) \] applied between the plates (Figure 1.2). The electric field between the plates is \[ E(t) = \frac{U(t)}{d_{\text{gap}}} = \frac{U_0}{d_{\text{gap}}} \cos(2 \pi f_0 t). \] A particle entering the gap with velocity \( v \) experiences an accelerating or decelerating field depending on the RF phase.

Transit-time condition

For effective acceleration, the field should not change sign while the particle is inside the gap. A simple estimate for the transit time is \[ t_{\text{cross}} \approx \frac{d_{\text{gap}}}{v}. \] The RF field reverses after half a period, \( T_0/2 = 1/(2 f_0) \). Requiring \( t_{\text{cross}} \lesssim T_0/2 \) yields the transit-time condition \[ d_{\text{gap}} \lesssim \frac{v}{2 f_0}. \] If this condition is satisfied, the particle reaches the exit aperture before the field reverses and leaves the capacitor with a net energy gain.

Even with RF voltages, however, we cannot raise \( U_0 \) to arbitrarily large values. Breakdown and power limitations still constrain the maximum field in a single gap. To reach higher energies we therefore need to reuse the same RF source in many gaps in series.

4. Widerøe structure: many gaps and drift tubes

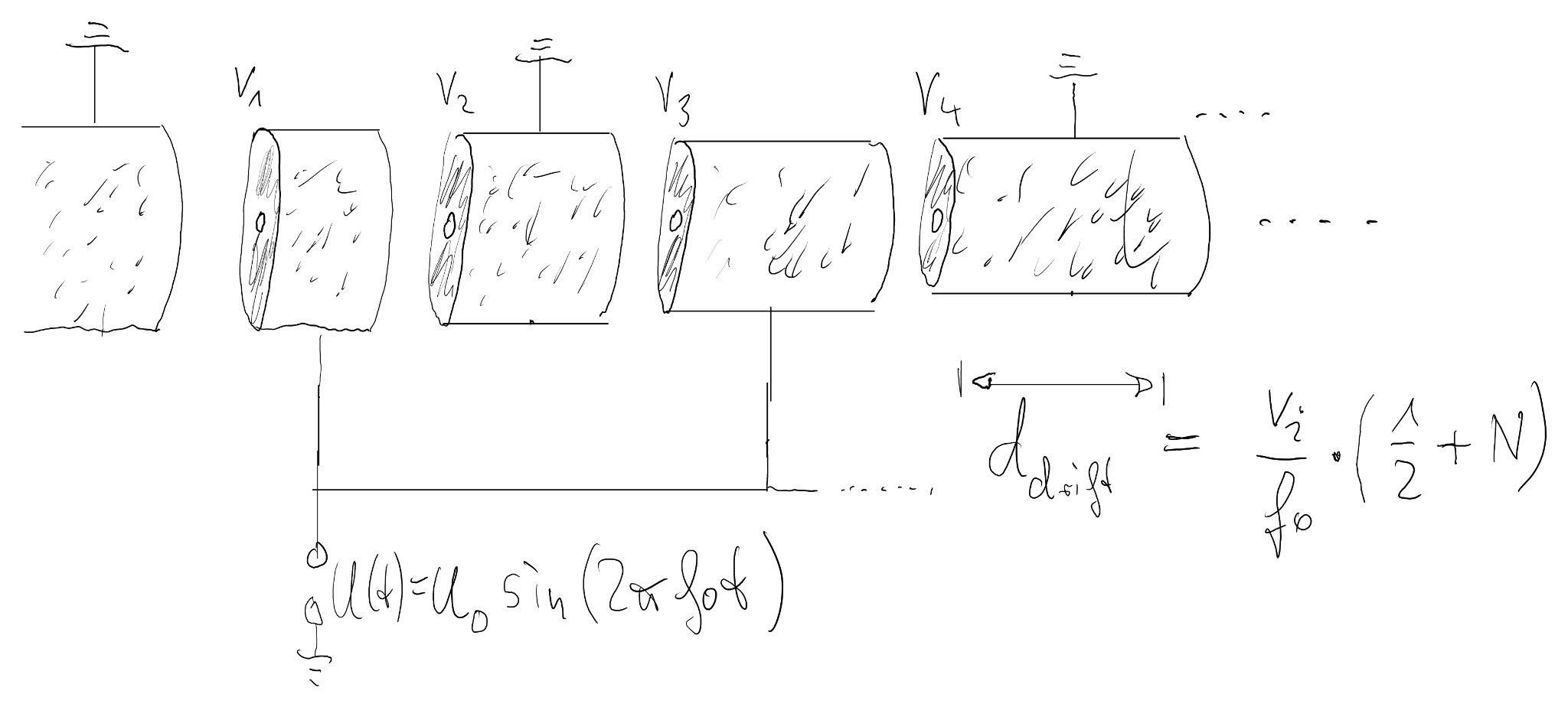

Rolf Widerøe proposed an elegant way to re-use an RF voltage for many acceleration steps. Metallic drift tubes shield the particle between the gaps, and the RF phase is adjusted such that each gap provides an accelerating kick (Figure 1.3). Historically, the Widerøe linac predates Lawrence's cyclotron but is closely related in spirit: in both cases the same RF source is used repeatedly while the particle energy increases.

Drift tubes and phase advance

Inside a drift tube the field is essentially zero and the particle moves at (approximately) constant velocity \( v \). The time the particle spends inside a given tube is \[ t_{\text{drift}} \approx \frac{d_{\text{drift}}}{v}, \] where \( d_{\text{drift}} \) is the tube length. While the particle is shielded, the RF field can change sign and prepare the next gap with the correct accelerating polarity. For the particle to arrive at the next gap in phase with the accelerating field, the drift time should be about half an RF period, or an odd multiple of it: \[ t_{\text{drift}} \approx \frac{1}{2 f_0}, \; \frac{3}{2 f_0}, \; \frac{5}{2 f_0},\;\ldots \] This translates into drift-tube lengths \[ d_{\text{drift}} \approx \frac{v}{2 f_0}, \; \frac{3 v}{2 f_0}, \; \frac{5 v}{2 f_0},\;\ldots \] In practice one typically chooses the shortest solution \( d_{\text{drift}} \approx v/(2 f_0) \) for a compact accelerator and lets the tubes become longer as the particle velocity increases.

In principle, we can now obtain arbitrarily high particle energies by adding more gaps and drift tubes. The total length of the accelerator then scales with the number of gaps and with the characteristic drift-tube length \( d_{\text{drift}} \). For ultra-relativistic particles with \( v \approx c \) this length has a simple lower bound: \[ d_{\text{drift}}^{\text{min}} \approx \frac{c}{2 f_0}. \] If we think in terms of electromagnetic waves rather than voltages, this is just half a free-space wavelength, \[ d_{\text{drift}}^{\text{min}} = \frac{\lambda}{2}, \qquad \lambda = \frac{c}{f_0}. \] This shows immediately how to make linear accelerators more compact: increase the RF frequency, i.e. decrease the wavelength.

5. Frequencies, wavelengths and the evolution of accelerators

Historically, the available technology for generating strong electromagnetic fields has evolved towards higher frequencies:

- Radio (1920s): commercial broadcasting operates from hundreds of kHz up to tens of MHz, corresponding to wavelengths from kilometers down to a few tens of meters. These frequencies were already available when first accelerator concepts were developed.

- Early accelerators (1930s): electrostatic machines such as Van de Graaff generators and Cockcroft–Walton supplies provided DC voltages of a few MV, while RF-driven structures like the Widerøe linac and the first cyclotrons used MHz-range fields to re-use the same voltage many times.

- Radar, TV, microwave technology (1940s–1950s): the invention of high-power microwave sources opened the GHz region (wavelengths of a few cm), enabling compact, high-gradient RF cavities for linacs and synchrotrons.

- Lasers (from 1960): Theodore Maiman operated the first working laser, a ruby laser, on 16 May 1960. Optical frequencies correspond to wavelengths of order micrometers. Modern high-power lasers, in particular chirped-pulse amplification systems, reach enormous electric field strengths in focus.

In terms of our simple drift-tube scaling \( d_{\text{drift}}^{\text{min}} \approx \lambda/2 \), this evolution means that the characteristic length scale of accelerating structures has shrunk from meters (radio frequencies) to centimeters (microwaves) and potentially to micrometers (optical and near-infrared lasers). The central theme of this lecture series is how to exploit these extremely high laser fields to build compact, laser-driven accelerators, in particular for ion acceleration in plasmas.

6. Interactive Widerøe accelerator simulator

The following interactive module,

lecture01_wideroe_simulator.html,

illustrates the concepts of RF gaps, transit time and drift tubes:

- Start with a single large gap and choose a very small frequency mimicing DC voltage to visualize uniform acceleration.

- Increse the RF frequency and observe how the particle oscillates if \( d_{\text{gap}} \) is too large. Play with the phase if you like, the time of injection has interesting effects.

- Reduce the gap length until \( d_{\text{gap}} < v/(2 f_0) \) and observe net acceleration, that is ejection of the particle from the gap.

- Add drift tubes with \( d_{\text{drift}} \approx v/(2 f_0) \) to build a multi-gap Widerøe structure and see how the energy grows with the number of gaps.