1. Basic laser concept: resonator, active medium, pump

To understand modern high-power, ultrashort-pulse lasers, we start from the basic ingredients of any laser:

- Active medium – provides optical gain via stimulated emission.

- Pump – supplies energy to create a population inversion.

- Optical resonator – cavity that selects and amplifies resonant modes.

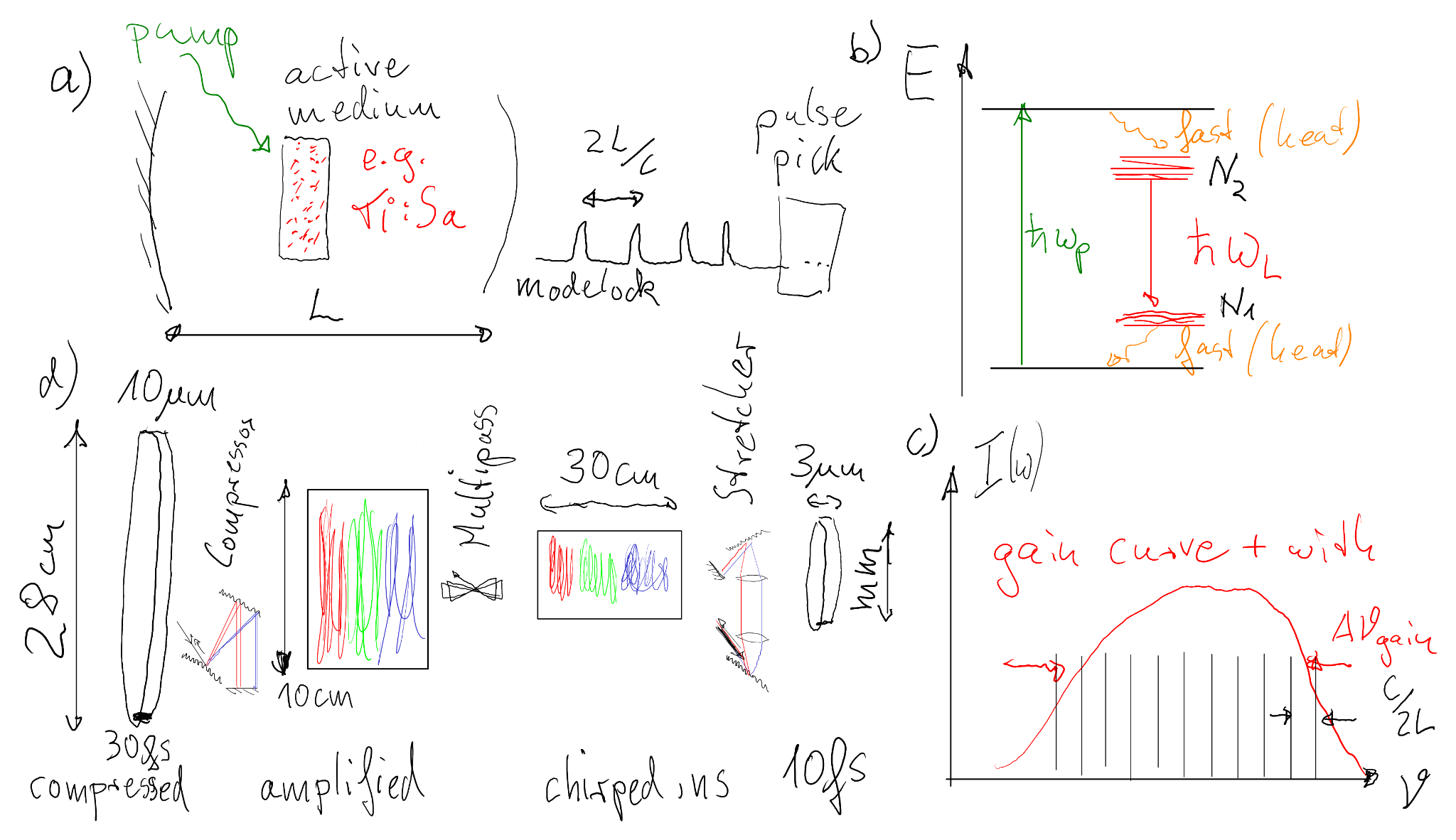

The pump (flashlamp, diode laser, or another laser) excites electrons in the active medium from lower-lying states to higher-lying energy levels. Stimulated emission then amplifies light at the transition between an upper and a lower laser level. The resonator mirrors reflect the light back and forth, so the light passes many times through the medium and experiences exponential gain until losses and gain balance in steady state. The upper left part of Figure 3.1 (panel (a)) shows this situation schematically: a gain medium inside a resonator with an external pump.

2. Energy levels and population inversion

A key requirement for laser action is population inversion: the number of atoms in the upper laser level must exceed the population of the lower laser level. This cannot be achieved in a simple two-level system. The upper right part of Figure 3.1 (panel (b)) sketches the idea of a multi-level laser medium.

2.1 Why a 2-level system cannot be inverted

In a two-level system, the pump and the laser transition connect the same states. Any pump process that excites atoms from the ground state to the excited state is counteracted by stimulated emission back to the ground state. At thermal equilibrium, the upper level is always less populated than the lower level; and even under strong pumping, the best we can do is equalize the populations, not invert them.

2.2 Three-level and four-level systems

A three-level system adds a higher pump level, from which atoms decay into the upper laser level. The lower laser level is the ground state. Inversion is possible, but only if more than half of all atoms are pumped out of the ground state. This requires high pump power and is not very efficient.

A four-level system adds an additional level below the lower laser level. The lower laser level then rapidly decays to this “true” ground state and is essentially empty. As a result, even a small population in the upper laser level yields inversion with respect to the lower level. Most practical lasers, including Ti:sapphire, operate in an effective four-level or quasi-four-level scheme, as indicated in Fig. 3.1(b).

3. Gain bandwidth and longitudinal modes

The active medium determines not only the central wavelength of the laser, but also its gain bandwidth. A particularly important medium for ultrashort pulses is Titanium:sapphire (Ti:sapphire), with a broad gain profile centered near 800 nm. The lower right part of Fig. 3.1 (panel (c)) illustrates this: a broad gain curve with discrete cavity modes (longitudinal modes) underneath.

A linear resonator of length \( L \) supports discrete longitudinal frequencies

\[ \nu_n = n \frac{c}{2L}, \qquad n = 1,2,3,\dots \]

The spacing between adjacent modes is \[ \Delta \nu = \frac{c}{2L}. \] Typically, many such modes lie within the gain bandwidth of the laser.

3.1 From many modes to short pulses: mode locking

If only one longitudinal mode oscillates, the laser output is essentially continuous-wave (CW). However, if many modes oscillate with fixed phase relationships (mode locking), the resulting field in the time domain is a train of short pulses. This is a direct consequence of the Fourier theorem: a broad spectrum of frequencies with a well-defined phase structure can interfere constructively in short time intervals.

In a Ti:sapphire oscillator, it is common to generate pulses with durations on the order of 20–100 fs at repetition rates of tens of MHz (often around 80 MHz). The output is then a train of equally spaced femtosecond pulses, as suggested in the time-domain sketch in Fig. 3.1(a).

4. From oscillator pulse to high energy: nonlinearities and damage

A single pulse from a mode-locked Ti:sapphire oscillator typically has:

- pulse energy \( \sim 1\,\text{nJ} \),

- pulse duration \( \sim 20\text{–}30\,\text{fs} \),

- beam diameter \( \sim 1\,\text{mm} \).

This is far too little energy for most applications. We therefore need to amplify the pulse by many orders of magnitude, up to the joule level. However, simply sending such a short, intense pulse through an amplifier chain would immediately cause problems:

- Nonlinear optical effects distort the pulse and beam.

- Optical damage can permanently destroy components.

4.1 Nonlinear polarization

The polarization response of a medium to an electric field \( E \) can be expanded as

\[ P(\mathbf r,t) = \chi^{(1)} E + \chi^{(2)} EE + \chi^{(3)} EEE + \cdots \]

At low intensities, the linear term \( \chi^{(1)} E \) dominates and the response leads to the well-known phenomena of linear optics (such as dispersion). At high intensities (high field strength), higher-order terms become important. In symmetric materials (most glasses and gases), the third-order term \( \chi^{(3)} E^3 \) is most relevant and gives rise to:

- Self-phase modulation (SPM) – intensity-dependent phase, spectral broadening.

- Self-focusing (Kerr effect) – intensity-dependent refractive index, beam collapse.

These effects are central to ultrafast optics: they can be used beneficially, for example in passive mode locking inside the oscillator (self-focusing acts like an intensity-dependent lens). However, in high-power amplifiers they are detrimental, because they distort the pulse and can lead to catastrophic damage.

4.2 Time scales of damage

The nature of damage depends on the pulse duration:

- Nanosecond pulses mainly cause thermal damage: heat diffusion, melting, cracking. Nonlinearities have time to feed into classical heating processes.

- Femtosecond pulses can drive “cold ablation”: electrons are ionized on a timescale too short for significant thermal diffusion; material is removed with minimal heat-affected zone.

For our purposes in laser-driven acceleration, we want to avoid nonlinearities and damage in the amplification chain and only exploit the extreme intensities in the final focus and the interaction region.

5. Chirped Pulse Amplification (CPA)

The lower left part of Fig. 3.1 (panel (d)) summarizes the concept of chirped pulse amplification (CPA). The central idea is to keep the intensity low during amplification. The intensity of a pulse is roughly

\[ I \approx \frac{E_{\text{pulse}}}{A\,\tau}, \]

where \( E_{\text{pulse}} \) is the pulse energy, \( A \) the beam area, and \( \tau \) the pulse duration. To reduce \( I \) while increasing \( E_{\text{pulse}} \), we do two things:

- Increase the beam area \( A \) by expanding the beam diameter.

- Increase the pulse duration \( \tau \) by stretching the pulse in time.

The implementation of CPA proceeds in three main steps, as indicated in Fig. 3.1(d):

5.1 Stretching

A single femtosecond pulse from the oscillator is sent through a grating stretcher or another dispersive system. Different frequency components of the pulse follow different optical paths, so that the pulse acquires a linear chirp and is stretched from tens of femtoseconds to hundreds of picoseconds or even nanoseconds. The peak intensity drops by many orders of magnitude.

5.2 Amplification

The stretched pulse is then amplified in several stages, typically in Ti:sapphire crystals pumped by energetic green laser pulses (e.g. frequency doubled Nd:YAG). At (almost) each stage, the beam diameter is increased to keep the fluence and intensity below the nonlinear limits (B-integral smaller than 1). The largest available amplifier crystals allow pulse energies up to tens of joules.

5.3 Compression

After amplification, the chirped pulse is sent into vacuum, expanded once more and then sent through a grating compressor, which is essentially the time-reversed version of the stretcher. The chirp is removed (red part of spectrum delayed wrt blue), and the pulse is recompressed to a duration close to its transform limit. The result is an ultrashort pulse with extremely high peak power (which requires propagation in "vacuum" to avoid non-linearities on transport to the experiments).

6. Example: the ATLAS-3000 laser at CALA

A concrete realization of this concept is the Advanced Titanium:Sapphire Laser (ATLAS-3000) at the Centre for Advanced Laser Applications (CALA) in Garching.

In simplified form, the pulse evolution in ATLAS proceeds as follows:

- Oscillator: A Ti:sapphire oscillator produces a train of femtosecond pulses at \( \sim 80\,\text{MHz} \). A single pulse from this train, with energy of order \( 1\,\text{nJ} \) and duration \( \sim 20\text{–}30\,\text{fs} \), is selected as the seed.

- Stretching: This seed pulse is pre-amplified (booster), stretched in a grating stretcher to a duration on the order of \( 1\,\text{ns} \), acquiring a linear chirp. The peak intensity is reduced dramatically.

- Multi-stage amplification: The stretched pulse is amplified in several Ti:sapphire stages. Along the chain, the beam diameter is expanded stepwise up to several tens of centimeters. Pulse energies of tens of joules are reached while keeping both fluence and intensity below damage thresholds and minimizing nonlinear distortions.

- Compression: The amplified, chirped pulse is recompressed in a large grating compressor to durations of below 30 femtoseconds (only 10 optical cycles). The available gain bandwidth allows pulse durations down to \( \sim 20\,\text{fs} \); in day-to-day operation, pulses of just below \( 30\,\text{fs} \) with energies between roughly \( 10 \) and \( 40\,\text{J} \) on target are typical.

- Focusing: Finally, the pulse is guided in vacuum to the experimental chambers. Off-axis parabolic mirrors focus the beam close to the diffraction limit: at the LION laser–ion acceleration beamline, a focus of order \( 5\,\mu\text{m} \) (FWHM) is achieved with an f-number of 5. At the LUX beamline, where the goal is maximum intensity (e.g. for photon–photon scattering studies), focusing with f-number 1 is pursued. For wakefield acceleration at ETTF, the focal length is of order 10 m!, HF works with 50 cm focal length.

The combination of short pulse duration (\( \sim 20\text{–}30\,\text{fs} \)), high energy (tens of joules), and tight focusing leads to peak powers beyond one petawatt. Focused to micrometer spot size, these conditions are sufficient to drive highly nonlinear, and in particular relativistic laser–plasma interactions, which form the basis of laser-driven electron and ion acceleration.