0. Overview

Consider the laser–target interaction at a moment when the laser has already reached its full intensity, while the electrons have not yet responded. This is, of course, an idealisation—it would require an essentially instantaneous rise of the laser intensity—but it provides a useful order-of-magnitude estimate. Radiation pressure (the Lorentz force associated with the laser fields) “snow-plows” the electrons forward. For simplicity we treat the ions as immobile, so an electrostatic field builds up until its restoring force balances the radiation-pressure force. A quasi-balanced state of this kind can be observed in 1D PIC simulations, especially for circular polarisation, which suppresses electron heating. For a clean demonstration, use heavy ions (e.g. \(m_i/m_e\sim 1000\)) to keep ions nearly stationary, circular polarisation, \(n_e\approx 10\,n_c\), and \(a\approx 5\).

Radiation pressure and the electron depletion layer

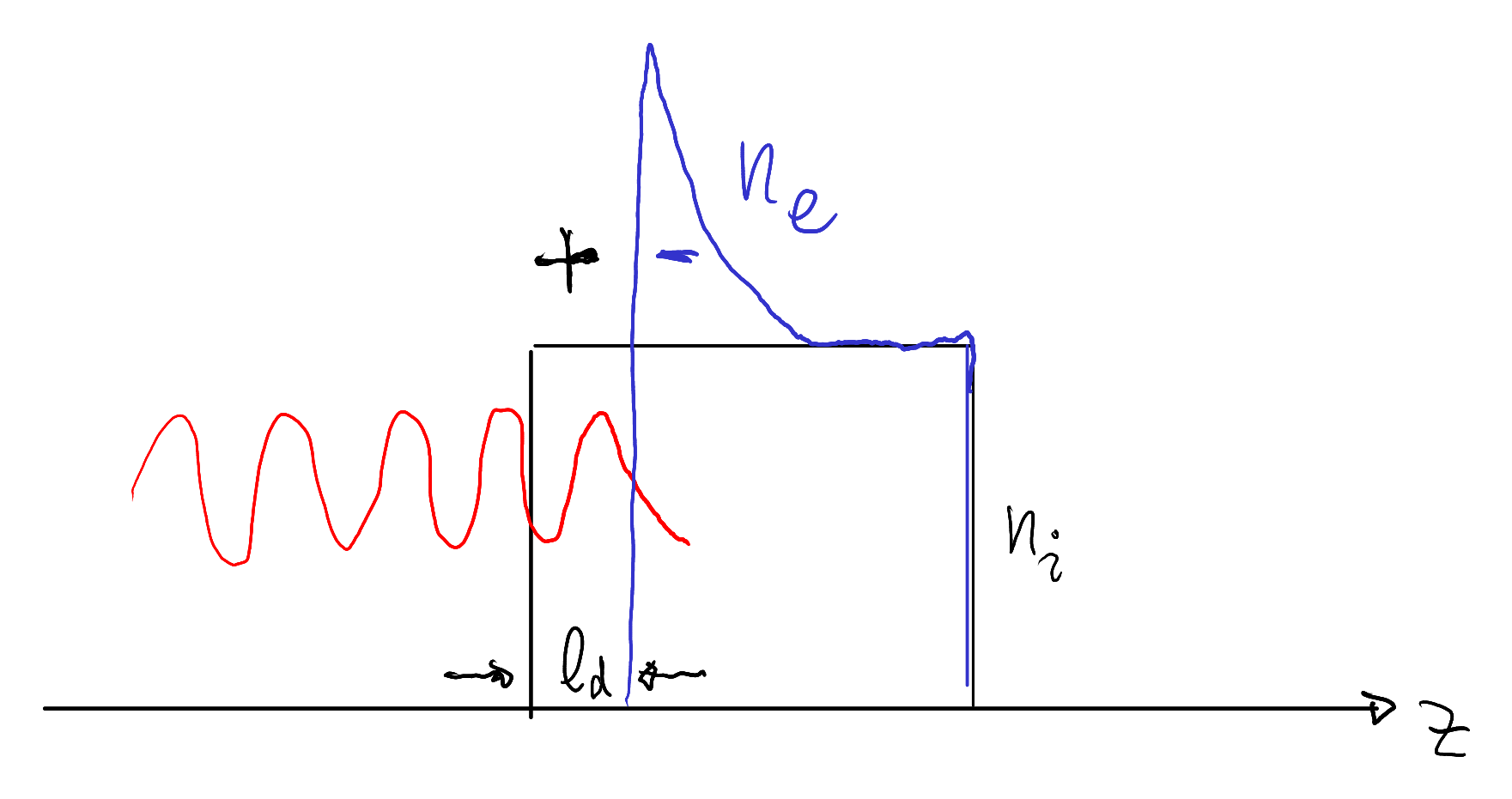

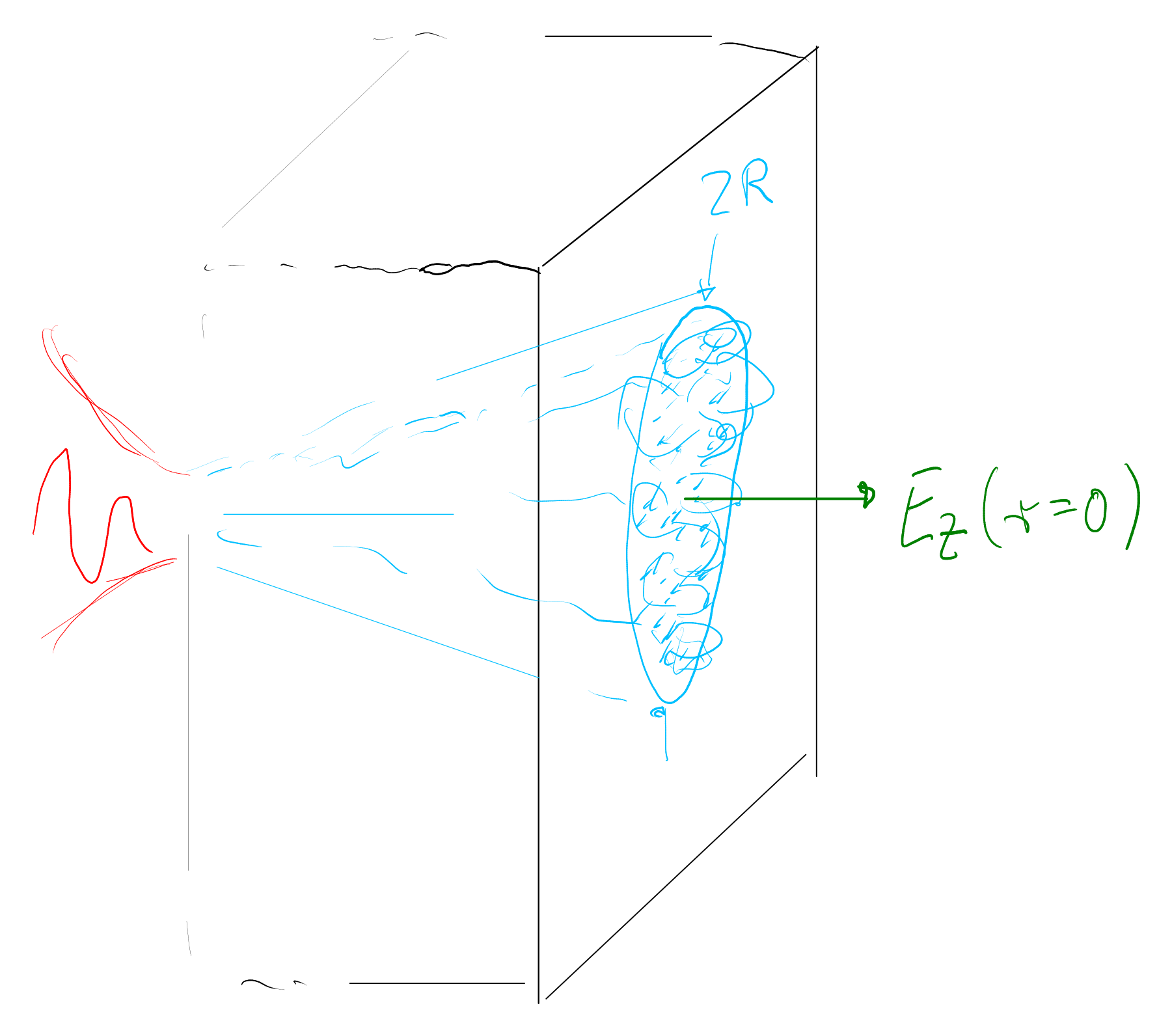

Figure 10.1 illustrates this force-balanced configuration and helps estimate the depletion-layer thickness \(l_{d}\) by balancing forces:

\[\begin{aligned} -\,eE_{z} &= -\,e\,v \times B \\ &\rightarrow\; \frac{e}{\epsilon_{0}}\,q_{i}n_{i}l_{d} = \frac{p_{\bot}}{\gamma}\frac{E_{L}}{c} \\ &\rightarrow\; \frac{e}{\epsilon_{0}}\,q_{i}n_{i}l_{d} = mc\,\frac{a_{L}}{\sqrt{1 + a_{L}^{2}}}\,\frac{m\omega_{L}c\,a_{L}}{ec} \end{aligned}\]

Hence

\[\frac{q_{i}n_{i}}{n_{c}}\frac{l_{d}}{\frac{\lambda}{(2\pi)}} = \frac{a_{L}^{2}}{\sqrt{1 + a_{L}^{2}}} \approx a_{L}\]

Another way to come up with a similar equation is by balancing radiation pressure (assuming reflectivity of 1) with the electrostatic pressure,

\[\epsilon_{0}E_{z}^{2} = \frac{2I}{c}\]

Which rewrites to

\[\frac{e^{2}}{\epsilon_{0}}q_{i}^{2}n_{i}^{2}l_{d}^{2} = \frac{2}{c}\epsilon_{0}c\left( \frac{m\omega c}{e} \right)^{2}a_{L}^{2}\]

And results in

\[\frac{q_{i}n_{i}}{n_{c}}\frac{l_{d}}{\frac{\lambda}{(2\pi)}} = \sqrt{2}a_{L}\]

This is close to the force-balance result, but it rests on a different physical assumption (electrostatic pressure rather than the explicit single-particle force balance). Compare the two derivations and identify where the numerical prefactor changes.

If the target is thinner than \(l_{d}\), the electrons cannot remain bound to the ions. If this electron removal happens sufficiently rapidly, the remaining ion cloud undergoes a Coulomb explosion. It is instructive to estimate the maximum energy that an ion can gain in a directed Coulomb explosion of a disc of radius \(R\), ion charge density \(q_{i}en_{i}\), and thickness \(l\ll R\).

Light sail acceleration

If the target thickness is close to the depletion-layer thickness, the displaced electron layer can assemble just behind the ions. This situation is favourable because a substantial fraction of the ions can be accelerated as a compact, quasi-neutral plasma bunch that remains dense (at least initially) and can still reflect the remainder of the laser pulse. This is the basic picture of light-sail acceleration: the laser pushes on the electron layer (the sail), which in turn drags the ions (the freight) via the charge-separation field. The field lines between electrons and ions act like “strings”. Assuming perfect reflection, the equation of motion for the sail is

\[\frac{dp}{dt} = \frac{2P(t)}{c}\frac{1 - \beta}{1 + \beta}\]

This can be solved for a constant laser power \(P\) applied over the pulse duration \(\tau_{L}\). The factor \(\ldiv{(1 - \beta)}{(1 + \beta)}\) captures the Doppler shift of the reflected light; the kinetic-energy gain is directly associated with the redshift of the reflected photons.

The non-relativistic equation is very instructive as it yields the sail velocity

\[\beta = \frac{v}{c} = \frac{2E_{L}}{Mc}\]

Here \(E_{L}=\int P(t)\,dt\) is the laser-pulse energy and \(M\) is the mass of the accelerated sail (plasma bunch). Note, however, that pushing to higher velocities by increasing \(E_{L}\) generally requires a heavier sail to keep the electrons bound. Since the depletion-layer thickness scales with \(a_{L}\), the minimum accelerable mass \(M\) scales similarly, and the sail velocity then increases only as \(\sqrt{E_{L}}\) (more precisely, \(\sqrt{I_{L}}\)).

Hole boring and ion ‘reflection’

For targets that are much thicker than the depletion layer (the common case), the reflecting interface propagates into the plasma. The ions in the depletion region are not truly inert; they are pulled forward by the charge-separation field. As the compressed electron layer advances into previously unperturbed material, fresh ions must be set in motion, which slows the interface. The result is a roughly steady propagation speed, the hole-boring velocity \(v_{B}\):

\[\frac{1}{2}m_{i}n_{i}v_{B}^{2} \approx \frac{2I}{c}\]

This suggests that an ion density spike will move through the target with velocity

\[v_{B} = \sqrt{\frac{4I}{m_{i}n_{i}c}}\]

This scenario is worth exploring with the provided interactive 1D PIC code (link to code).

Note that the density cannot be reduced arbitrarily, even though the expression above would suggest ever larger velocities. The laser must first establish a reflecting (overdense) interface, i.e. the electron density \(n_{e}=q_{i}n_{i} > n_{c}\) must exceed the critical density.

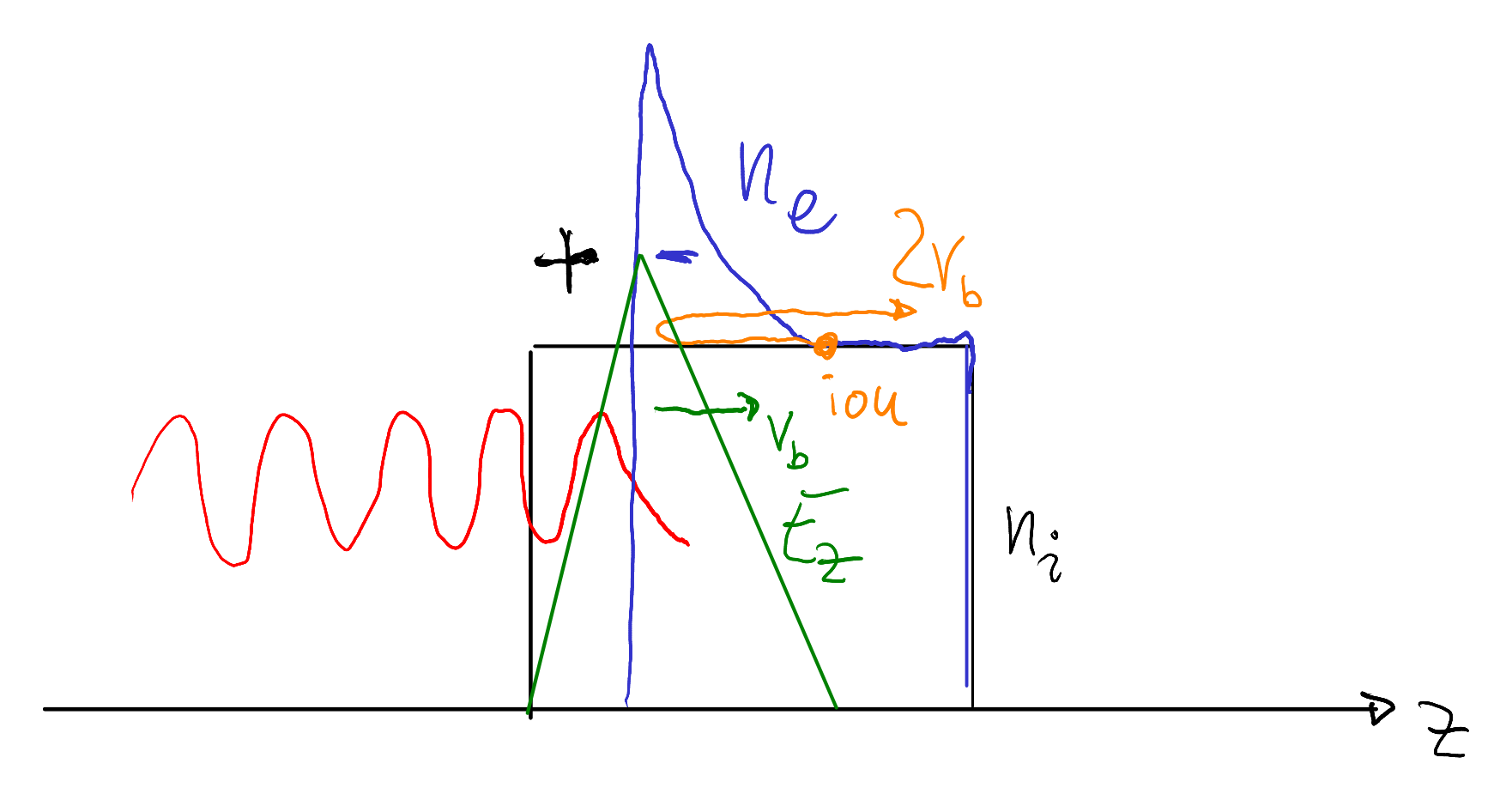

In simulations (e.g. \(n_{e}=10n_{c}\), \(a=4\), circular polarisation) you will find ions that move faster than \(v_{B}\). The hole-boring front carries an electric field that propagates through the plasma at \(v_{B}\). Ions initially at rest can be picked up by this moving field and accelerated to roughly twice that speed, \(2v_{B}\). In the frame of the hole-boring front this is simply a reflection process—much like a tennis ball gaining speed from a moving racket.

All of the above relies on the idealisation that no laser energy is absorbed (i.e. no conversion into heat). If the absorption were 100%, momentum transfer would still occur: the force on the electrons would change from \(\ldiv{2P}{c}\) (perfect reflection) to \(\ldiv{P}{c}\) (perfect absorption). In reality, absorption produces energetic (“hot”) electrons that traverse the target and drive expansion—often the dominant mechanism behind laser-driven ion acceleration.

The hot electrons do not remain confined to the depletion layer; they propagate through the target. Nearby cold electrons rearrange to maintain quasi-neutrality and are heated in the process, so the bulk electron population becomes warm. In such a warm plasma the ion-acoustic speed (the speed at which ion-density perturbations propagate)

\[c_{i} = \sqrt{\frac{q_{i}k_{B}T_{e}}{m_{i}}}\]

can exceed the hole-boring velocity. In that case a collisionless shock can form and propagate. Its effect is similar to a moving hole-boring front: ions from the background plasma can be reflected by the shock and reach velocities of order \(2c_{i}\).

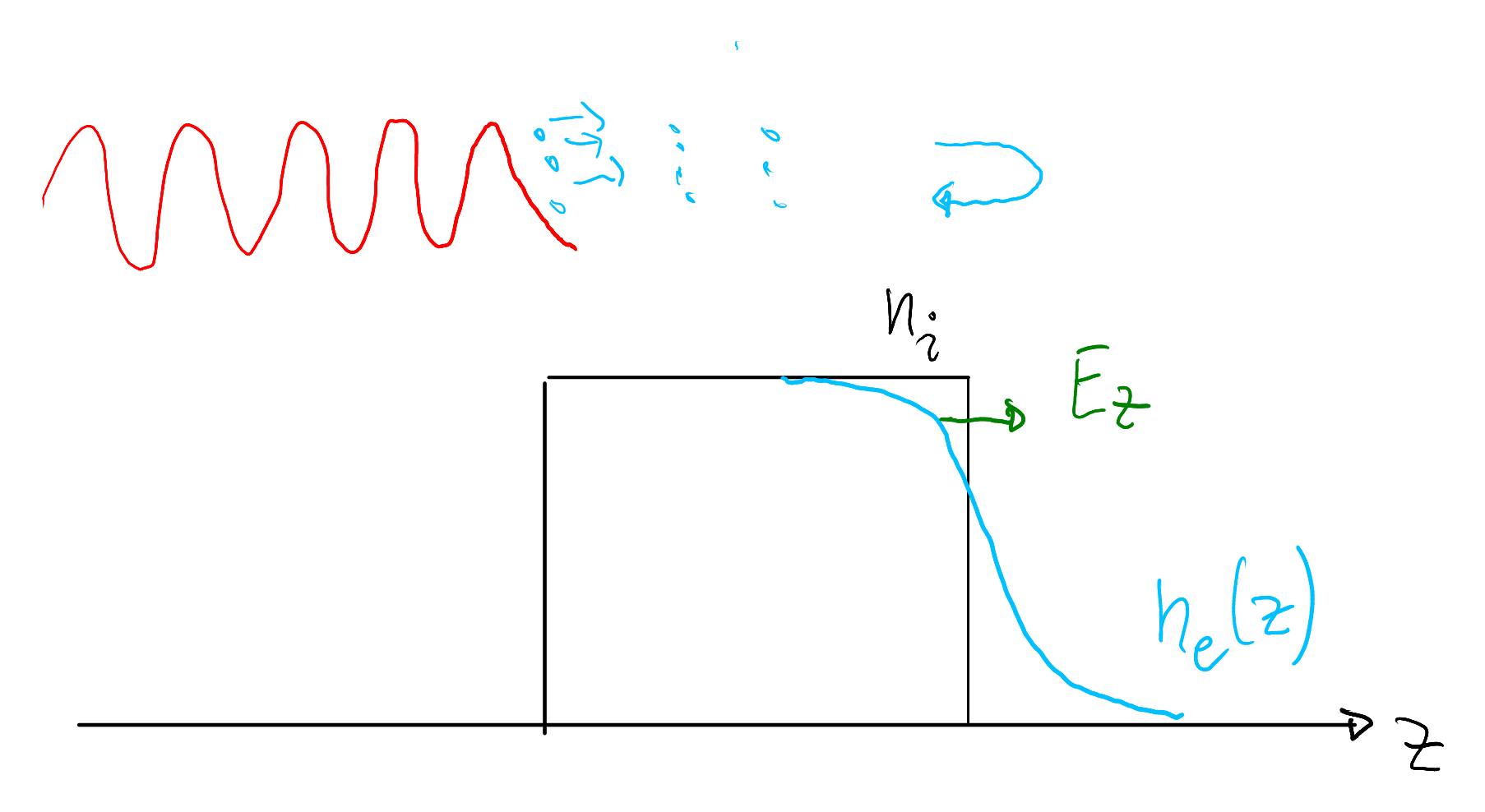

Rear-side sheath formation and hot-electron density

The main source of fast ions—especially for targets that are thick compared to the depletion layer—is the rear surface, where the ion density drops most abruptly. In an idealised picture the ions remain cold while hot electrons traverse the foil, so the rear-side ion profile is initially close to a step function. Hot electrons streaming into vacuum set up a strong potential that can trap a significant fraction of the hot-electron population, despite their high energy: many electrons turn around and re-enter the target. After a short transient it is reasonable to assume that the outgoing and returning electron fluxes balance.

In this quasi-steady situation the hot-electron density profile is approximately stationary and in (quasi-)thermal equilibrium with the electrostatic potential \(\Phi\):

\[n_{e} = n_{e,0}\exp\left\{ \frac{e\phi}{E_{e}} \right\}\]

Where \(E_{e}\) is the average energy of hot electrons, the particle density of hot electrons can be approximated by

\[n_{e,0} = \frac{N_{h}}{\pi R^{2}v_{e}\tau_{L}}\]

Here \(v_e\) is the characteristic hot-electron speed; typically \(v_e \approx c\) for relativistic electrons.

We assume that \(N_{h}=\frac{\eta E_{L}}{E_{e}}\) electrons are heated by converting a fraction \(\eta\) of the laser energy \(E_{L}\) into electrons of average kinetic energy \(E_{e}\). We further assume that these electrons are produced over the pulse duration \(\tau_{L}\), propagate with speed close to \(c\), and are distributed over an approximately circular area of radius \(R\).

Figure 10.3 sketches the rear-side density configuration in a 1D model. Hot electrons of density \(n_{e,0}\) escape into vacuum, leaving a positive surface charge. The associated field decelerates the electrons; many turn around and re-enter the plasma. After a short time an equilibrium develops in which the outgoing and returning electron fluxes balance. In this state the electron density \(n_{e}(z)\) is in thermal equilibrium with the electrostatic potential and is supported by a step-like ion distribution \(n_{i}(z)=n_{i,0}=\frac{n_{e,0}}{Z}\) for \(z<0\) and \(n_{i}(z)=0\) for \(z\ge 0\), which is taken to be fixed initially. Formulating and solving the corresponding Poisson equation is a good exercise. (Assume a Boltzmann distribution for the hot electrons with \(E_{e}=k_{B}T_{h}\). Tip: see, e.g., Crow et al. (1975) and Mora (2003).)

In the vacuum region, the potential \(\varphi = \frac{e\Phi}{E_{e}}\) reads

\[\varphi(\zeta > 0) = - \ln{\left( 1 + \frac{\zeta}{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}} \right)^{2} - 1} = - 2\ln{\left( 1 + \frac{\zeta}{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}} \right) - 1}\]

\[\lambda_{D} = \sqrt{\frac{\epsilon_{0}E_{e}}{n_{e,0}e^{2}}}\]

The maximal electric field (at the boundary) is

\[E_{s}(\zeta = 0) = \frac{E_{e}}{e\lambda_{D}}\ \sqrt{\frac{2}{\exp(1)}}\]

Mora expansion model vs. test-particle estimate

Crow et al. and Mora ("Plasma expansion into a vacuum", Phys. Rev. Lett. 90 (2003) 185002) studied numerically how the ion front evolves during expansion into vacuum and what maximum velocities can be reached. Mora derived a compact expression for the maximum ion velocity:

with \(c_{s} = \left( \frac{q_{i}E_{e}}{m_{i}} \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}\) the ion acoustic velocity and \(\tau = \frac{\omega_{pi}t}{\left( 2\exp(1) \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}}\) where \(\omega_{pi} = \left( \frac{n_{e0}q_{i}e^{2}}{\left( m_{i}\epsilon_{0} \right)} \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}\) is the ion plasma frequency.

As a simple comparison, consider a test ion moving in a fixed sheath potential: we assume the potential does not evolve in time and ask how much energy an ion starting at \(z=0\) could gain. For an ion of charge \(q_{i}e\) we can then write \(E_{k}=q_{i}E_{e}\left(\varphi(\zeta=0)-\varphi(\zeta>0)\right)\), and hence

\[E_{k}(\zeta) = 2q_{i}E_{e}\ln\left( 1 + \frac{\zeta}{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}} \right)\]

And for the velocity

\[v = 2c_{s}\sqrt{\ln\left( 1 + \frac{\zeta}{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}} \right)} = \frac{dz}{dt} = \frac{\lambda_{D}d\zeta}{\frac{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}}{\omega_{pi}}d\tau} = \frac{c_{s}}{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}}\frac{d\zeta}{d\tau\ }\]

With some further rearrangement—using \(\frac{z}{\lambda_{D}}=\zeta=\zeta_{i}\sqrt{2\exp(1)}\) and the normalised time \(\tau=\frac{t\omega_{pi}}{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}}\)—we obtain

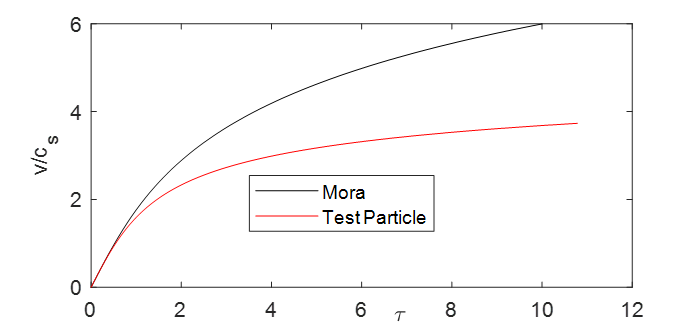

Figure 10.4 compares the expansion-front velocity from Eq. (1) with the numerical solution of the test-particle model defined by Eq. (2). Both expressions grow without bound as \(t\rightarrow\infty\), reflecting the idealisations of the models.

In practice the acceleration is finite: one often truncates it after an effective acceleration time \(t_{a}\) of order the pulse duration (see, e.g., Fuchs Nat. Phys. 2006). Many works have revisited this expansion scenario; for planar foils, however, the basic descriptions remain largely 1D.

It is therefore natural to consider a slightly more realistic geometry. Suppose the rear-side sheath forms as above, with electrons streaming out, turning around, and streaming back into the target, but only within a finite transverse region of radius \(R\). Figure 10.5 sketches this configuration.

The Poisson equation can still be written and, in principle, solved numerically. However, a useful first estimate follows by considering only the positive charge and neglecting the electrons: the potential of a uniformly charged thin disc is straightforward to compute, especially on axis where the acceleration is maximal.

The potential is

\[\Phi\left( \mathbf{r} \right) = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\int_{}^{}{\frac{Zen\left( \mathbf{r}^{\prime} \right)}{\left| \mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}^{\prime} \right|}d^{3}\mathbf{r}^{\prime}}\]

where the ion number density \(n\left( \mathbf{r}^{\prime} \right) = n_{0}\) is constant within the disc volume, \(e\) is the electron charge, and \(Z\) the charge number. On axis we have \(\mathbf{r} = (0,0,z)\), and we are interested In \(z \geq 0\), and \(\left| \mathbf{r} - \mathbf{r}^{\prime} \right| = \left( r^{'2} + \left( z - z^{'} \right)^{2} \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}\) where \({r^{'}}^{2} = x^{'2} + y^{'2}\) is the radial distance to the axis. Then we can write

\[\begin{aligned} \Phi(z) &= \frac{Zen_{0}}{4\pi\epsilon_{0}}\int_{0}^{R}{\int_{- d}^{0}{\frac{2\pi r^{'}}{\sqrt{r^{'2} + \left( z - z^{'} \right)^{2}}}dr^{'}dz^{'}}} \\ &= \frac{Zen_{0}}{2\epsilon_{0}}\int_{- d}^{0}\left\lbrack \sqrt{R^{2} + \left( z - z^{'} \right)^{2}} - \left( z - z^{'} \right) \right\rbrack dz^{'} \\ &= \frac{Zen_{0}R^{2}}{2\epsilon_{0}}\int_{\zeta}^{\zeta + \delta}\left\lbrack \sqrt{1 + {\zeta^{'}}^{2}} - \zeta^{'} \right\rbrack d\zeta^{'} \\ &= \frac{Zen_{0}R^{2}}{2\epsilon_{0}} \cdot \frac{1}{2}\left\lbrack \zeta^{'}\left( \sqrt{1 + {\zeta^{'}}^{2}} - \zeta^{'} \right) + \tanh^{- 1}\left( \frac{\zeta^{'}}{\sqrt{1 + {\zeta^{'}}^{2}}} \right) \right\rbrack_{\zeta}^{\zeta + \delta} \end{aligned}\]

where we substituted \(\zeta^{'} = \frac{\left( z - z^{'} \right)}{R}\) and wrote \(\zeta = \ldiv{z}{R}\) as well as \(\delta = \ldiv{d}{R}\). For \(z = 0\), i.e. at the surface, we have

\[\Phi(0) = \frac{Zen_{0}R^{2}}{4\epsilon_{0}}\left\lbrack \delta\left( \sqrt{1 + \delta^{2}} - \delta \right) + \tanh^{- 1}\left( \frac{\delta}{\sqrt{1 + \delta^{2}}} \right) \right\rbrack\]

where \(\delta = \ldiv{d}{R}\) and we can calculate the potential. For \(z \rightarrow \infty\) the potential tends to zero. Therefore, if we place an ion with charge \(q_{i}e\) at \(z = 0\), it could gain the kinetic energy

\[E_{i,\infty} = q_{i}e\Phi(0)\]

The expression is a bit cumbersome and it is worthwhile approximating \(\delta = \ldiv{d}{R} \ll 1\). Then, we can approximate the potential as

\[\Phi(z) = \frac{Zen_{0}R^{2}}{2\epsilon_{0}}\int_{\zeta}^{\zeta + \delta}\left\lbrack \sqrt{1 + {\zeta^{'}}^{2}} - \zeta^{'} \right\rbrack d\zeta^{'} \approx \frac{Zen_{0}Rd}{2\epsilon_{0}}\left\lbrack \sqrt{1 + \zeta^{2}} - \zeta \right\rbrack\]

and then

\[E_{i,\infty} \approx q_{i}\frac{Ze^{2}n_{0}Rd}{2\epsilon_{0}}\]

The kinetic energy is then a function of distance \(\zeta\), via

\[E_{kin}(z) = q_{i}e\left\lbrack \Phi(0) - \Phi(z) \right\rbrack \approx E_{i,\infty}\left\lbrack 1 + \zeta - \sqrt{1 + \zeta^{2}} \right\rbrack\]

and we can calculate the distance over which the ion gains half the maximum kinetic energy via

\[E_{kin}\left( z_{\frac{1}{2}} \right) = \frac{E_{i,\infty}}{2} = E_{i,\infty}\left\lbrack 1 + \zeta_{\frac{1}{2}} - \sqrt{1 + \zeta_{\frac{1}{2}}^{2}} \right\rbrack\]

and it is

\[\zeta_{\frac{1}{2}} = \frac{3}{4}\]

How long does it take the proton to gain half of this energy? Let us calculate non-relativistic and judge later how wrong the conclusions will be. The non-relativistic velocity of the ion with mass \(m_{i}\) is

\[v(z) = \sqrt{\frac{2E_{kin}(z)}{m_{i}}} = v_{i,\infty}\sqrt{1 + \zeta - \sqrt{1 + \zeta^{2}}}\]

Then we can write

\[\frac{dz}{dt} = v\left( z(t) \right)\]

and with \(z = R\zeta\) separation of variables yields

\[\int_{0}^{\zeta}\frac{Rd\zeta^{'}}{v\left( \zeta^{'} \right)} = \int_{0}^{t}{dt^{'}}\]

The integral is

\[t = \frac{R}{v_{i,\infty}}\left\lbrack \sqrt{1 + \zeta - \sqrt{1 + \zeta^{2}}}\left( 1 - \frac{1}{2\left( \zeta - \sqrt{1 + \zeta^{2}} \right)} \right) + \frac{1}{2}\tanh^{- 1}\sqrt{1 + \zeta - \sqrt{1 + \zeta^{2}}} \right\rbrack\]

We can put in \(\zeta = \ldiv{3}{4}\) from before and calculate the time, but it is more useful to clean up this expression beforehand by recalling that

\[\sqrt{1 + \zeta - \sqrt{1 + \zeta^{2}}} = \frac{v}{v_{i,\infty}} = \left( \frac{E_{k}}{E_{i,\infty}} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}} = X\]

With this definition and the abbreviation for a “ballistic acceleration time” \(\tau_{0} = \frac{R}{v_{i,\infty}}\), we can reformulate to

\[\frac{t}{\tau_{0}} = X\left( 1 + \frac{1}{2}\frac{1}{1 - X^{2}} \right) + \frac{1}{2}\tanh^{- 1}X\]

(This is the expression and main result of the publication Schreiber PRL 2006.) The time it takes to gain half of the maximally possible energy is obtained for \(X = \left( \ldiv{1}{2} \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}\) and is \(t_{\ldiv{1}{2}} = 1.85\tau_{0}\).

Of course, you notice at least one weakness; that is when \(E_{i,\infty}\) becomes comparable to the rest energy of the accelerated ion. Then we should solve the relativistic equation of motion. (see below)

However, the main point here is that even for infinite acceleration time, the accelerated ion gains only a finite kinetic energy. It is still necessary to truncate the acceleration after a certain time \(t_{a}\). Although this might be motivated by the fact that the field is maintained only for as long as the laser delivers fresh electrons (that is \(t_{a} \approx\) pulse duration as before), the assumption is quite ad hoc. Both Fuchs (based on Mora’s plasma expansion formula) and Schreiber (based on coulomb repulsion in a charged disc) explain observed proton energies in TNSA acceptably well. Schreiber model yields finite energies even for infinite acceleration times (due to the 3D charge distribution), this has some intriguing consequences such as the prediction of an optimum pulse duration for a given laser pulse energy.

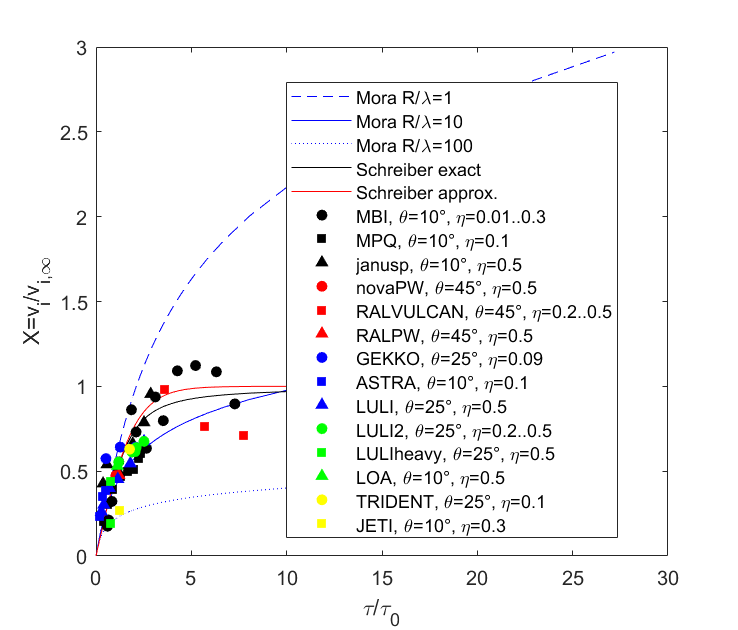

However, both models, Mora (or better Fuchs) as well as Schreiber (and many others, I apologize for not reviewing them all) can catch the crude order of magnitude of achievable ion energies in plasma expansion. Figure 10.6 aids the Mora/Fuchs and Schreiber comparison, (including an approximation that was later also used by Zeil 2010). In order to make this comparison, the 1D model requires an appropriate choice of radius \(R\) (here in units of laser wavelength \(\lambda\)).

Exercise: approximating Schreiber and comparing to Mora

If you want to understand or reproduce this figure, the following exercise might be helpful.

Problem statement:

Mora has demonstrated that the formula

\[v_{i} \approx 2c_{s}\ln\left( \tau + \sqrt{1 + \tau^{2}} \right) = 2c_{s}\sinh^{- 1}\tau\]

For the maximum ion velocity, with \(c_{s} = \left( \frac{ZE_{e}}{m_{i}} \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}\) the ion acoustic velocity and \(\tau = \frac{\omega_{pi}t}{\left( 2\exp(1) \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}}\) where \(\omega_{pi} = \left( \frac{n_{e0}Ze^{2}}{\left( m_{i}\epsilon_{0} \right)} \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}\) is the ion plasma frequency fits well to the evolution of a plasma front expanding into plasma. This equation by Mora is much simpler than the one by Schreiber (question 1), which reads

\[\frac{\tau_{L}}{\tau_{0}} = X\left( 1 + \frac{1}{2}\frac{1}{1 - X^{2}} \right) + \frac{1}{2}\tanh^{- 1}X\]

where \(X = \frac{v_{i}}{v_{i,\infty}}\), \(\tau_{0} = \frac{R}{v_{i,\infty}}\), and \(v_{i,\infty} = \left( \frac{2ZE_{\infty}}{m_{i}} \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}\) with \(E_{\infty} = mc^{2}\left( \frac{2\eta P_{L}}{P_{R}} \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}\). \(m_{i}\) is the mass of accelerated ion, \(Z\) its charge, \(m\) is the electron mass.

Find an approximate formula for the Schreiber model by Taylor-expanding in \(X\). Compare the “Mora” result with the exact “Schreiber” and the approximation, that is, make an appropriate plot in python where you plot \(\frac{v_{i}}{c_{s}}\) as function of \(\tau\) for Mora and \(\frac{v_{i}}{v_{i,\infty}}\) as function of \(\frac{\tau_{L}}{\tau_{0}}\) for the two Schreiber-model functions.

Solution:

Taylor expansion yields

\[X\left( 1 + \frac{1}{2}\frac{1}{1 - X^{2}} \right) + \frac{1}{2}\tanh^{- 1}X \approx 2X + \frac{2}{3}X^{3} + \frac{3}{5}X^{5} + \ldots\]

and the Taylor series of

\[\tanh^{- 1}X \approx X + \frac{1}{3}X^{3} + \frac{1}{5}X^{5} + \ldots\]

So it seems that the function is dominated by the \(\tanh^{- 1}X\) term and that we can approximate

\[v_{i} \approx v_{i,\infty}\tanh\left\lbrack \frac{\tau_{L}}{2\tau_{0}} \right\rbrack\]

The Mora formula is

\[v_{i} = 2c_{s}\sinh^{- 1}\left\lbrack \frac{\omega_{pi}}{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}}\tau_{L} \right\rbrack\]

For comparing we must relate the characteristic constants to one another. For the sake of simplicity, we make the comparison for protons and assume \(\eta = 1\). In Mora, the characteristic velocity is the sound velocity

\[c_{s} = \left( \frac{E_{e}}{m_{i}} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\]

and in Schreiber it is the maximally possible terminal velocity

\[v_{i,\infty} = \left( \frac{2E_{\infty}}{m_{i}} \right)^{\frac{1}{2}}\]

Comparison hence boils down to relating \(E_{e} = mc^{2}\left( 1 + \frac{I_{L}\lambda^{2}}{I_{0,\lambda^{2}}} \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}\) to \(E_{\infty} = mc^{2}\left( \frac{2P_{L}}{P_{R}} \right)^{\ldiv{1}{2}}\) and this is not possible in general, because for \(c_{s}\) the intensity \(I_{L}\) matters and this requires the choice of a certain radius \(r_{L}\) along with the laser power \(P_{L}\). In Schreiber, we do not need the value \(E_{e}\)! However, this relation then reads

\[\frac{E_{e}}{E_{\infty}} = \sqrt{\frac{1 + \frac{{2P}_{L}\lambda^{2}}{\pi^{2}P_{R}R^{2}}}{\frac{2P_{L}}{P_{R}}}} = \sqrt{\frac{P_{R} + {2P}_{L}\frac{\lambda^{2}}{\pi^{2}R^{2}}}{2P_{L}}} \approx \frac{\lambda}{\pi R}\]

if we assume intensities well beyond the relativistic threshold. Hence, the pre-factors relate as

\[\frac{2c_{s}}{v_{i,\infty}} = \sqrt{\frac{2E_{e}}{E_{\infty}}} \approx \sqrt{2\frac{\lambda}{\pi R}}\]

Comparing the time scales of Mora

\[\frac{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}}{\omega_{pi}} = \sqrt{\frac{m_{i}\epsilon_{0}}{n_{e0}e^{2}}}\]

and Schreiber

\[\tau_{0} = \frac{R}{v_{i,\infty}} = \sqrt{\frac{m_{i}R^{2}}{2E_{\infty}}} = \sqrt{\frac{m_{i}R^{2}}{2E_{\infty}}}\]

requires calculating the hot electron density

\[\begin{aligned} n_{e0} &= \frac{N_{e}}{\pi R^{2}c\tau_{L}} \\ &= \frac{\eta E_{L}}{E_{e}\pi R^{2}c\tau_{L}} \\ &= \frac{\eta P_{L}}{E_{e}\pi R^{2}c} \\ &= \frac{2\epsilon_{0}}{R^{2}e^{2}}\frac{E_{\infty}^{2}}{E_{e}} \end{aligned}\]

Then

\[\frac{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}}{\omega_{pi}} = \sqrt{\frac{m_{i}R^{2}}{2E_{\infty}}\frac{E_{e}}{E_{\infty}}} = \tau_{0}\sqrt{\frac{E_{e}}{E_{\infty}}} \approx \tau_{0}\sqrt{\frac{\lambda}{\pi R}}\]

When comparing the two models, we hence must make a choice for \(\ldiv{\lambda}{R}\), that is how strong we focus the laser. Let us plot \(\frac{\tau}{\tau_{0}}\) on the x-axis, then a certain value relates to the argument in the Mora-formula via

\[\frac{\tau\omega_{pi}}{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}} = \frac{\tau}{\tau_{0}}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}} \cdot \sqrt{\frac{\pi R}{\lambda}}\]

With the relation between \(c_{s}\) and \(v_{i,\infty}\), the Mora formula can be written as

\[X_{MORA} = \frac{v_{i}}{v_{i,\infty}} = \frac{\sqrt{2}}{C}\sinh^{- 1}\left( \frac{\tau}{\tau_{0}} \cdot \frac{C}{\sqrt{2\exp(1)}} \right)\]

with the scale factor

\[C = \sqrt{\frac{\pi R}{\lambda}}\]

Optimisation over the years and the quest for light sail acceleration

Most TNSA experiments and models benefit from reducing the target thickness. Achieving this experimentally required substantial technical progress, in particular improved temporal contrast to prevent premature expansion of thin foils before the main pulse arrives.

As the foil becomes thinner, the distinction between front-side and rear-side acceleration becomes less clear: the corresponding fields can eventually overlap. Moreover, once the thickness approaches the (relativistic) skin depth, significant laser transmission is expected. These regimes—where partial transparency becomes important—have been studied extensively in simulations and experiments. Relevant concepts include (leaky) light-sail acceleration, break-out afterburner, relativistically induced transparency, magnetic vortex acceleration, and others.

A key control parameter across these scenarios is the target thickness itself. In the idealised limit of perfect contrast and an abrupt turn-on of the laser field, the depletion-layer thickness provides a lower bound. If the target is thinner, electrons can be stripped from the ions and the remaining ion cloud primarily accelerates via Coulomb explosion (for sudden, complete electron removal you can estimate the maximum ion energy from the uniformly charged-disc model above).

In the optimum case, the radiation-pressure-driven electron layer stalls and can drag the ions forward via the charge-separation field. Electrons form the (light) sail, ions are the freight, and the field lines are the strings. The resulting quasi-neutral plasma bunch behaves like a mirror that is pushed by the laser.

For a laser pulse with power \(P\) reflected from a “sail” with mass \(M\), the momentum follows

\[\frac{dp}{dt} = \frac{2P}{c}\frac{1 - \beta}{1 + \beta}\]

and with \(p = Mc\gamma\beta\) and abbreviating \(t_{0} = \frac{Mc^{2}}{(2P)}\) we have

\[\frac{d\gamma\beta}{dt} = \frac{1}{t_{0}}\frac{1 - \beta}{1 + \beta}\]

Substitute \(t_{ret} = t - \int_{0}^{t}{\beta\left( t^{'} \right)dt^{'}}\) (‘retarded’ here represents the time when photons were emitted to reach the sail by time \(t\)).

\[\frac{d\gamma\beta}{dt} = \frac{d\gamma\beta}{dt_{ret}} \cdot \frac{dt_{ret}}{dt} = (1 - \beta)\frac{d\gamma\beta}{dt_{ret}} = \frac{1}{t_{0}}\frac{1 - \beta}{1 + \beta}\]

and therefore

\[\frac{d\gamma\beta}{dt_{ret}} = \frac{1}{t_{0}(1 + \beta)} = \gamma^{3}\frac{d\beta}{dt_{ret}} = \frac{1}{1 - \beta^{2}}\gamma\frac{d\beta}{dt_{ret}} = \frac{1}{(1 - \beta)(1 + \beta)}\gamma\frac{d\beta}{dt_{ret}}\]

Hence,

\[\frac{d\beta}{dt_{ret}} = \frac{1}{t_{0}}\frac{1 - \beta}{\gamma} = \frac{1}{t_{0}}(1 - \beta)\sqrt{1 - \beta^{2}}\]

with the solution

\[\frac{T_{ret}}{t_{0}} = \int_{0}^{\beta_{m}}\frac{d\beta}{(1 - \beta)\sqrt{1 - \beta^{2}}} = \sqrt{\frac{1 + \beta_{m}}{1 - \beta_{m}}} - 1\]

When we associate \(T_{ret}\) with the pulse duration \(\tau_{L}\), we can write

\[\tau = \frac{\tau_{L}}{t_{0}} = \frac{2P\tau_{L}}{Mc^{2}} = \frac{2E_{L}}{Mc^{2}}\]

And the terminal velocity

\[\beta_{m} = \frac{(1 + \tau)^{2} - 1}{(1 + \tau)^{2} + 1}\]

As always, it is instructive (but not necessary) to consider non-relativistic velocities, then

\[\beta_{m} \approx \frac{2E_{L}}{Mc^{2}}\]

That is, the velocity of a sail is proportional to the ratio of reflected laser energy to rest energy of the sail.

One might hence attempt to simply minimize the mass of the sail to maximize velocity, but here is the crux: The larger the intensity (and hence the larger the energy), the larger is the required thickness of the “sail”, and hence its mass. If we recall the depletion layer thickness from the beginning of this lecture, you note that

\[M_{\min} \propto d_{\min} \propto \sqrt{I_{L}} \propto \sqrt{E_{L}}\]

And therefore, the maximum velocity in light sail acceleration will scale as well \(\propto \sqrt{E_{L}}\) only, and the kinetic energy \(\propto E_{L}\). This scaling seems more beneficial than typical TNSA scaling. However, it is worth noting (and it was explicitly noted by Karl Zeil et al.) that for very short pulses, TNSA energies scale \(\propto E_{L}\) as well.