0. Why this lecture?

Lecture 8 showed (with 1D PIC examples) that a laser can drive complex plasma dynamics. Lecture 10 will describe ion acceleration processes (expansion → TNSA → RPA), typically assuming that a fraction of the laser energy is converted into kinetic energy of “hot” electrons.

Goal of Lecture 9: explain how electromagnetic energy can be transferred to electrons in a plasma. This is the missing link between “laser hits plasma” and “hot electrons exist”.

1. Why a free electron does not absorb (cycle average)

A single free electron in a monochromatic plane wave performs quiver motion. In the simplest picture, the velocity stays phase-related to the electric field such that the cycle-averaged work vanishes: \(\langle -e\,\mathbf{E}\cdot\mathbf{v}\rangle = 0\).

Key idea: absorption requires a mechanism that breaks the perfect phase relation between field and motion: collisions, a boundary, a density gradient, or relativistic effects.

2. Collisional absorption (inverse Bremsstrahlung)

Collisions randomize momentum and introduce an effective friction. A minimal model includes a collision frequency \(\nu\):

\(m\,\dot{\mathbf{v}} = -e\,\mathbf{E}(t) - m\nu\,\mathbf{v}.\)

For a harmonic field \(\mathbf{E}(t)=\Re\{\mathbf{E}_0 e^{-i\omega t}\}\), the response is

\(\mathbf{v}(t)=\Re\left\{\frac{-e\,\mathbf{E}_0}{m(\nu-i\omega)}e^{-i\omega t}\right\}.\)

The phase lag yields nonzero cycle-averaged absorbed power per electron:

\(\langle P\rangle=\left\langle -e\,\mathbf{E}\cdot\mathbf{v}\right\rangle =\frac{e^2}{2m}\,\frac{\nu}{\omega^2+\nu^2}\,|\mathbf{E}_0|^2.\)

Interactive tool: phase lag and normalized absorption vs. collision frequency

We plot the normalized factor \(f(\nu/\omega)=\frac{\nu/\omega}{1+(\nu/\omega)^2}\) that appears in the simple damping model. It peaks at \(\nu/\omega = 1\) with value \(1/2\).

PIC note: without a collision operator, this channel is absent. With collisions, you need an additional scattering / momentum-randomization step (model dependent).

3. Collisionless absorption at the vacuum–plasma boundary

Many relevant mechanisms are collisionless and happen near the vacuum–plasma interface. Even for overdense plasmas, the field penetrates evanescently into a skin layer and drives currents there. Interface physics and the density gradient strongly influence absorption.

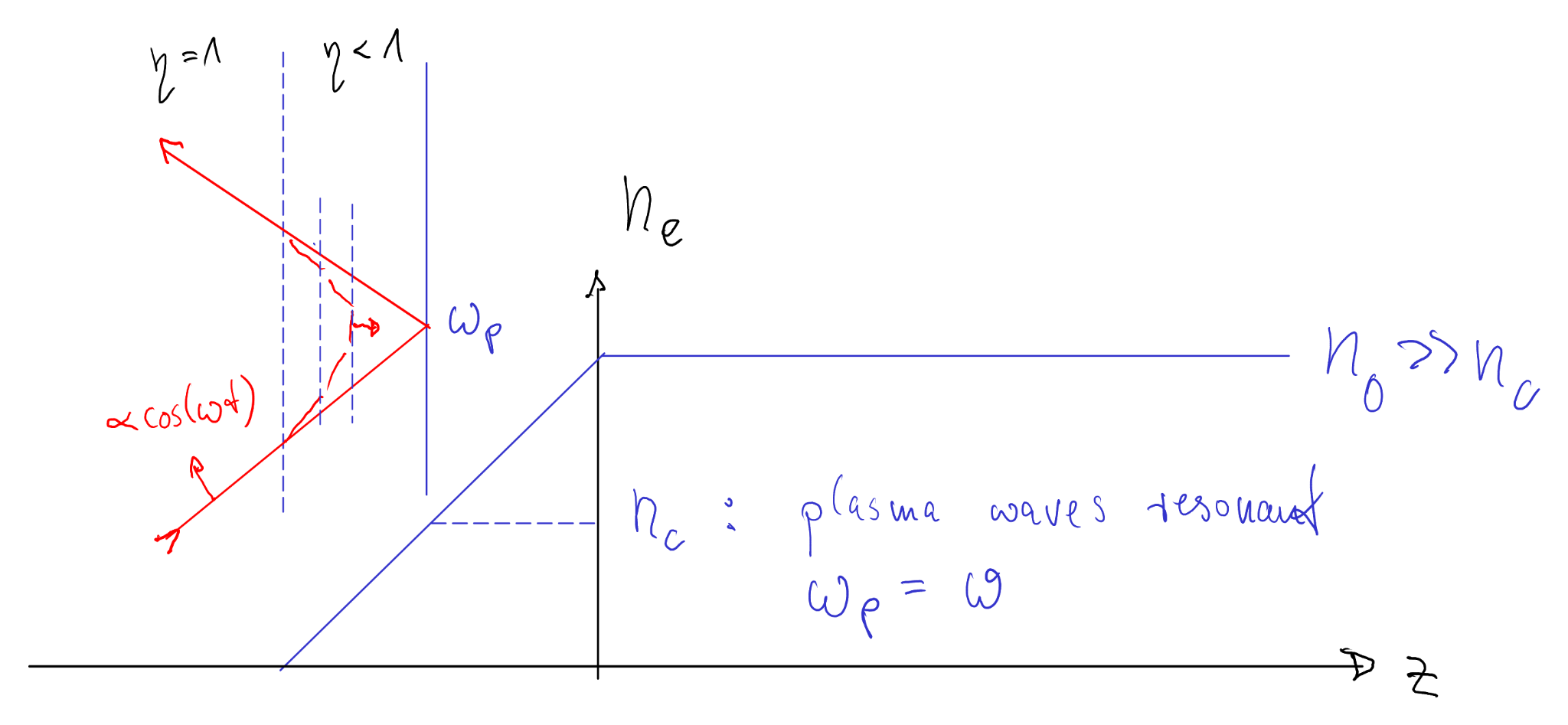

4. Resonance absorption (long scale length)

Recall the cold-fluid turning-point picture: in an inhomogeneous plasma the local refractive index can be written as \(n^2(x)=1-\omega_p^2(x)/\omega^2\). At the critical density (\(\omega_p=\omega\), i.e. \(n_e\approx n_c\)) the refractive index tends to zero and the wave reaches a turning point; beyond it the field becomes evanescent.

In practice, pre-expansion produces a finite density scale length \(L=\left|\frac{n_e}{\nabla n_e}\right|\). Resonance absorption is favored for sufficiently long gradients (compared to the skin depth) and oblique incidence with p-polarization.

For sufficiently long gradients, the laser reaches a turning point near \(n_e\approx n_c\). At oblique incidence with p-polarization, the field has a component along the density gradient and can resonantly drive an electron plasma wave at the critical surface. Dissipation of this plasma wave (e.g. Landau damping, wave breaking) transfers energy to electrons.

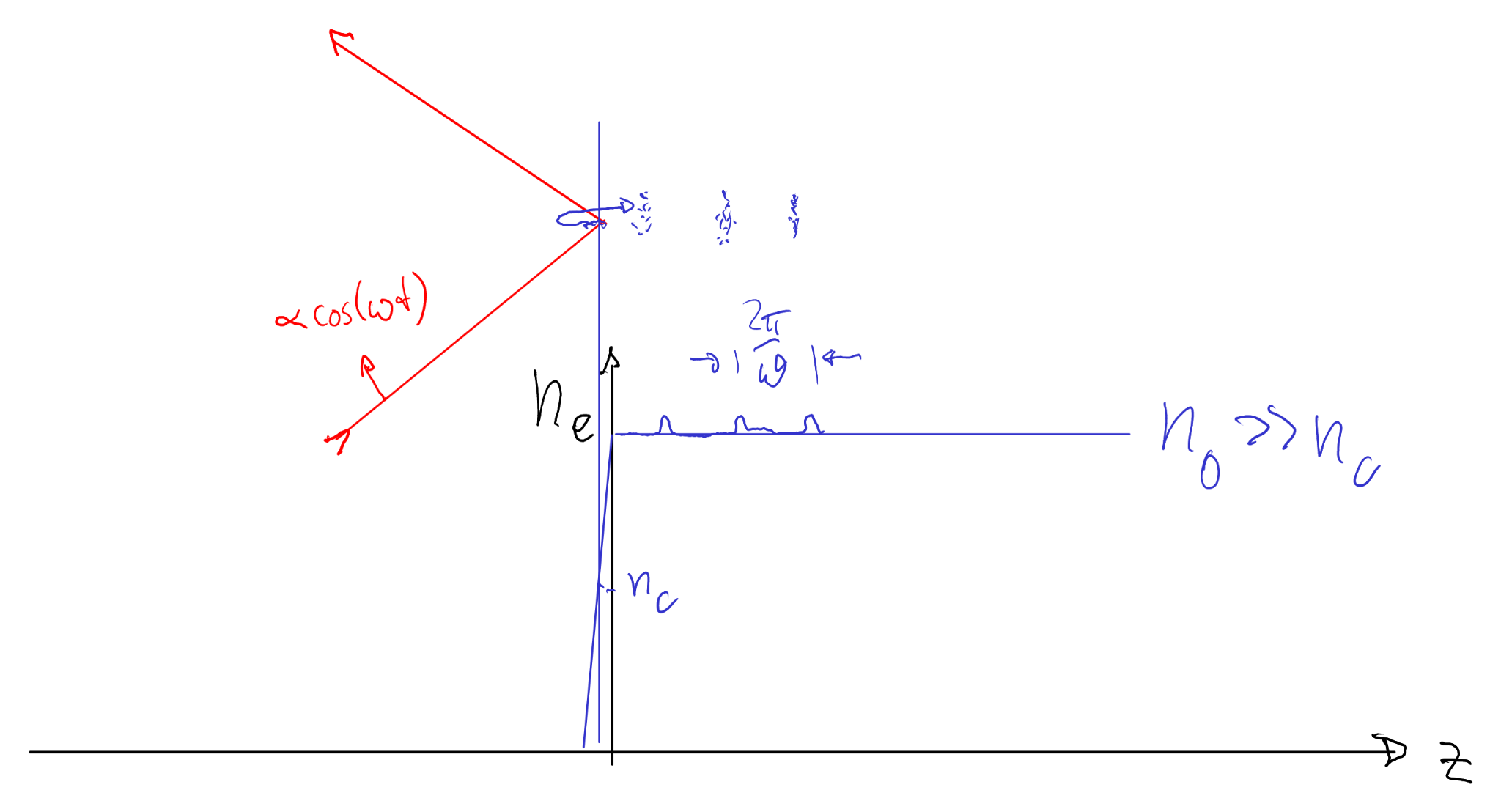

5. Vacuum / Brunel heating (short scale length)

For a very steep interface, the oscillating normal field can pull electrons into vacuum and push them back into the plasma. The result is injection of energetic electron bunches once per laser cycle.

A useful scale is the quiver amplitude \(x_{osc}=v_{osc}/\omega\) with \(v_{osc}=eE_0/(m\omega)\). A “sharp” boundary roughly means \(L\ll x_{osc}\).

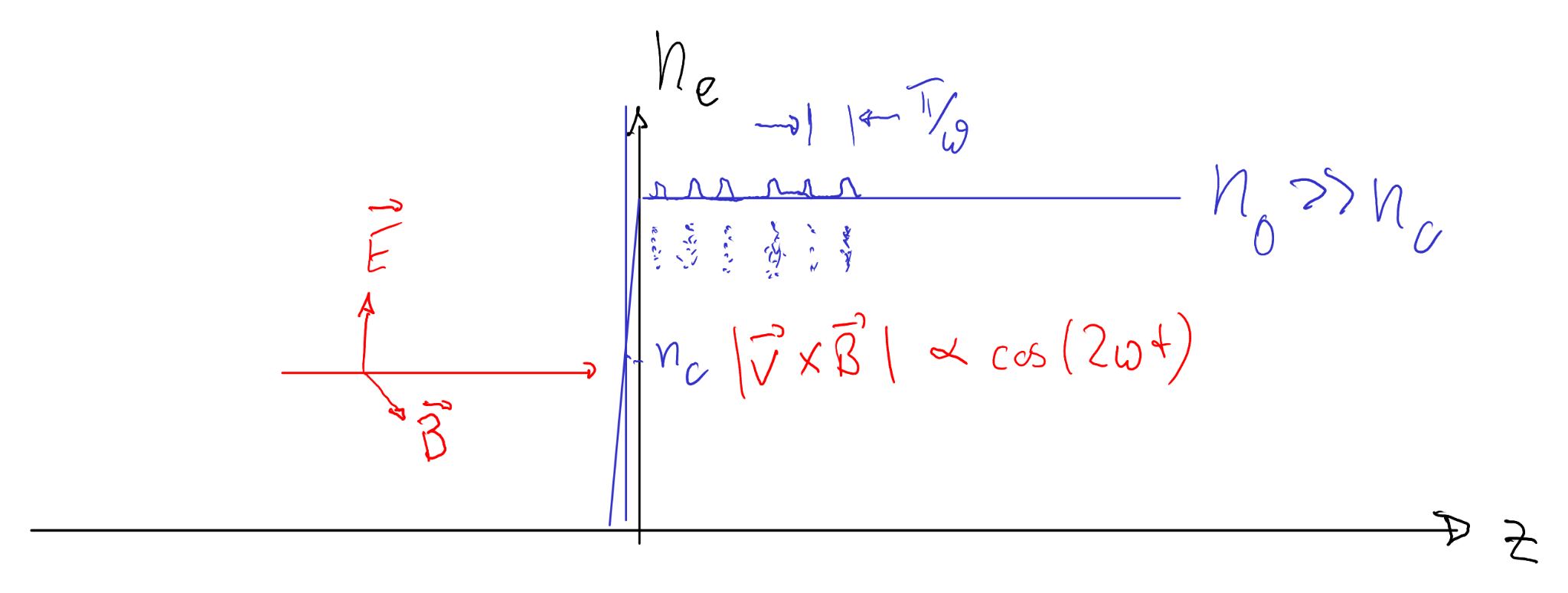

6. Relativistic \(j\times B\) heating

At relativistic intensity (\(a_0\gtrsim 1\)), magnetic forces matter. Even at normal incidence with linear polarization, the Lorentz force term \(-e\,\mathbf{v}\times\mathbf{B}\) generates a longitudinal push and produces electron bunches at \(2\omega\).

Connection to Lecture 8 (PIC): strong normal-incidence absorption at high \(a_0\) can occur even when non-relativistic resonance/vacuum arguments predict little — the magnetic term provides an additional phase-breaking channel.

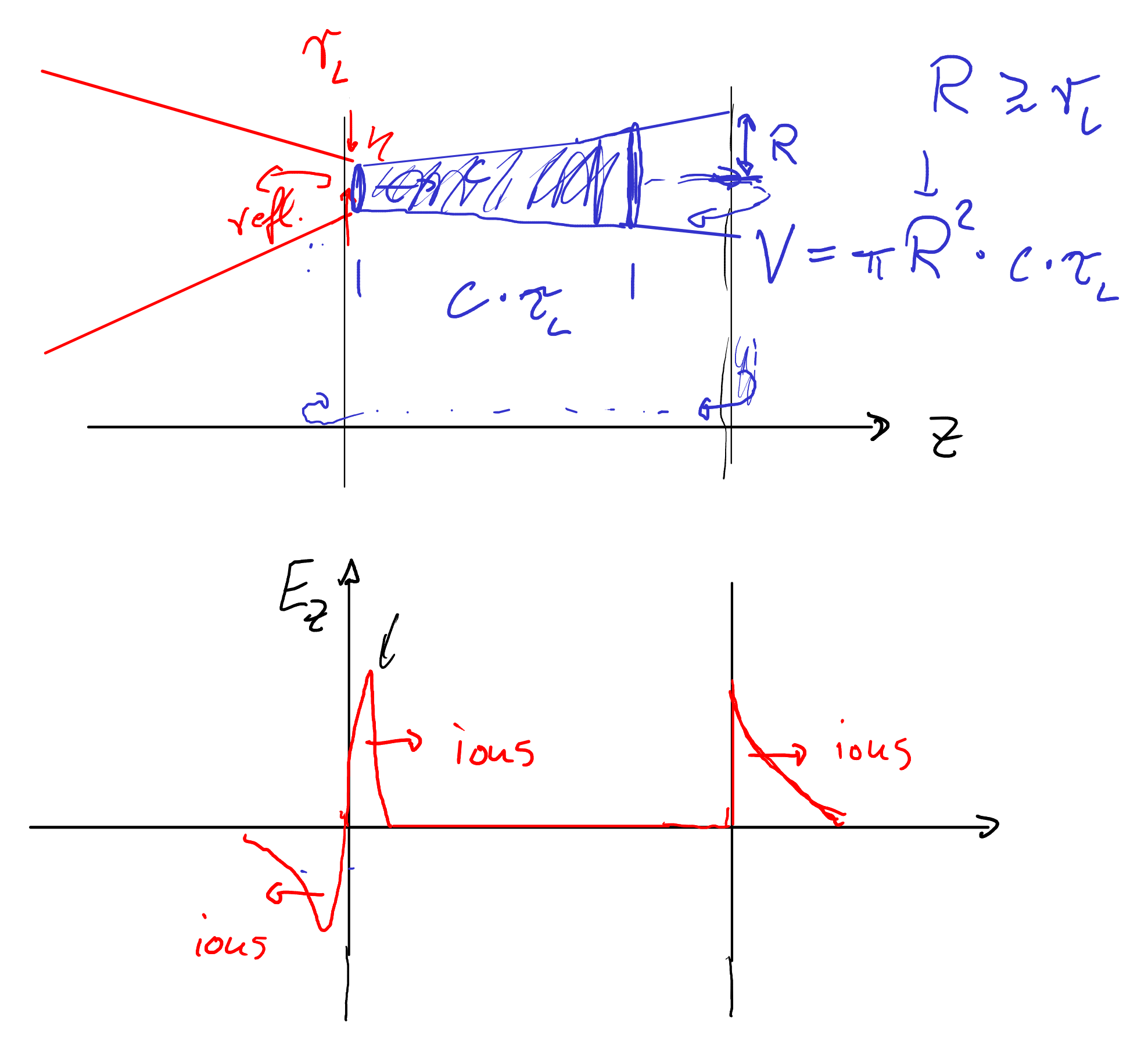

7. Bridge to ion acceleration (Lecture 10)

In Lecture 10 we will not model absorption microscopically. Instead, we treat it via an absorption fraction \(\eta\) and characterize the resulting electron population (often by an effective temperature \(T_h\) and a source size/divergence). These electrons set up quasi-static electrostatic fields responsible for ion acceleration.

8. Summary

- Ideal free electron: no net absorption without phase breaking.

- Collisions introduce a phase lag \(\Rightarrow\) inverse Bremsstrahlung absorption.

- At interfaces, gradients and boundary motion enable collisionless absorption.

- Resonance absorption: long gradients + oblique p-pol drive a plasma wave near \(n_c\).

- Vacuum/Brunel: sharp boundary pulls electrons into vacuum and reinjects hot bunches.

- Relativistic \(j\times B\): magnetic force enables strong absorption at high \(a_0\) (including normal incidence).

- At normal incidence, \(j\times B\) oscillates with \(2\omega\) for linear polarisation, but is constant for circular ("no" heating).